#14 June 1777

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

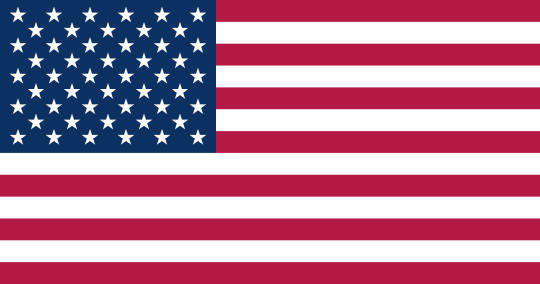

National Flag Day

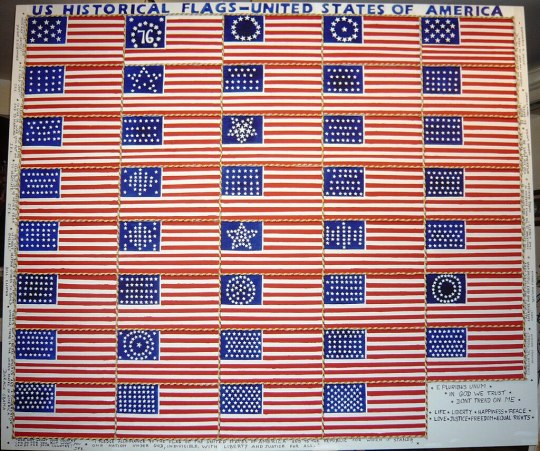

America’s Flag Day marks the Second Continental Congress’s adoption of the first U.S. national flag on June 14, 1777. The first flag featured the same 13 red and white stripes we see today. However, the number and arrangement of stars have changed as the number of states has increased over the centuries. The current flag has remained the same since 1960. Will we ever go from 50 to 51? Read on for a look at some possible statehood candidates. And consider this a warmup for Independence Day — in just 20 days.

Flag Day timeline

1776–1777 First American Flag Created

Continental Congressman Francis Hopkinson designs a United States flag and a flag for the U.S. Navy, however, Hopkinson's naval flag becomes the preferred National flag and the Continental Marine Committee sponsors the U.S. Flag Resolution on June 14, 1777.

1916 President Woodrow Wilson Recognizes Flag Day

Celebrating the selection of the first American flag back in 1777, President Wilson signs off on establishing June 14 of each year as Flag Day.

July 4, 1960 The Current U.S. Flag is Completed

The 50th star, representing Hawaii (not Alaska), completes the flag flown in the U.S. today.

July 20, 1969 The U.S. Flag Sees the Moon

There are now six U.S. flags present on the moon, but the first was placed by Neil Armstrong in 1969.

Flag Day Activities

Plan a costume contest as part of a BBQ

Teach your kids or less informed friends a history lesson

Make a healthy patriotic snack

The stars and stripes aren't just for flags anymore. Take the opportunity on Flag Day to sport the red, white, and blue on socks, bathing suits, and hairstyles. It's a perfect day to celebrate your patriotism with a fun twist.

An American flag trivia game is a quick and easy way to learn a few tidbits. Most people know that each star represents a state, but do they know that a new star only appears on July 4 following a state's admission to the Union? Trivia - bam!

Strawberries, blueberries, marshmallows, OH MY! Some of our favorite fruits lend themselves very well to creating flag-themed cakes, so roll with it. Fine, marshmallows aren't a fruit, but they're basically a summer necessity, so we'll let it slide.

5 American Flags — By The Numbers

50 — and counting

49

48

31

13

We've been at 50 for nearly 60 years. Possible candidates for the 51st star? Puerto Rico, Guam, and Washington, DC.

Seven times seven? A perfect square. There's just so much luck in this flag, we need to thank Alaska (January 1959) for joining us. This one had a short reign. Hawaii (August 1959) would soon make it 50.

It featured such beautiful symmetry with the addition of New Mexico and Arizona in 1912 and flew proudly for 47 years.

The number 31 doesn't easily lend itself to neat patterns. If we didn't actually love California (added in 1850) so much, we'd probably have made it secede after seeing the lack of symmetry. (This flag lasted seven years!)

America's original flag, it's the only one that dared defy the straight line pattern of all its successors. If you ask us, the 13 stars in a circle better represent the unity of the, uhhhh, union.

Why We Love Flag Day

A chance to show patriotism

Parades

It reminds us summer is near

It's easy to get so caught up in our day-to-day lives that we sometimes forget to be thankful for the bigger picture. Flag Day reminds us that we are one country — united — despite our disagreements.

Americans love to have parades for many events and holidays. Mid-June is the perfect time to set up that camping chair on the street corner and watch the local firefighters, school bands and dance troupes strut their stuff.

The weather is starting to behave, kids are wrapping up school, and BBQ season is upon us. Flag Day gives us another reason to celebrate outside and enjoy the sunshine.

Source

#Bend#Maryhill#Charlie Lake#Canada#Turnbull Wine Cellars#Oakville#Stars and Stripes#US Flag#14 June 1777#anniversary#US history#Flag Day#FlagDay#Chicago#architecture#USA#cityscape#Flight 93 National Memorial#DeWitt#New York City#Manhattan#Annapolis#tourist attraction#landmark#vacation#travel#original photography#Paoli Battlefield Site and Parade Grounds#St. Helena#Malvern

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

June 14th is Flag Day! 🇺🇸

It commemorates the adoption of the flag of the United States on June 14, 1777 by resolution of the Second Continental Congress.

Pictured above: U.S. Marines from Echo Company, 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment, pose holding an American flag shortly before leaving Patrol Base Khodi Rhom in Garmsir District of Helmand province in Afghanistan, April 20, 2010.

(Photo by Lance Cpl. Dwight A. Henderson)

179 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edward, Viscount (later Earl) Ligonier

Artist: Thomas Gainsborough (British, 1727-1788)

Date: 1770

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, CA, United States

Artwork Description

In this full-length portrait, Lord Ligonier is shown next to his horse. In his right hand, which rests on the horse's saddle, the sitter holds a black and gold-laced hat, while his left hand is on his sword hilt.

Biography

Edward Ligonier, a soldier, was born in 1740, the only son of Anne (Murray) Freeman, a widow, and Francis Augustus Ligonier (1693-1746), a French Protestant refugee who came to England in 1710 and rose to the rank of colonel in the 13th Dragoons and 59th Foot (infantry). Following his father's death from a battle wound in 1746, Edward was raised by his uncle, John Ligonier (1680-1770), who was promoted that year to the full rank of general and made commander-in-chief in Great Britain. Like his father and uncle, Edward Ligonier pursued a career in the army. In 1752, aged twelve, he entered the 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen's Bays) as a cornet, and from 1757 he served as lieutenant in the 7th Dragoons. He was aide-de-camp to Prince Ferdinand of Brunswick in the Seven Years' War, and on August 15, 1759 was promoted to captain of the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards. Appointed aide-de-camp to George III in 1763, he traveled to Madrid as secretary to Lord Rochford's special embassy (1763-65).

On December 16, 1766 Ligonier married Penelope Pitt, eldest daughter of George Pitt and his wife Penelope Atkins, at the British Embassy in Paris. On his uncle's death, April 27, 1770, he succeeded to the title of 2nd Viscount Ligonier of Clonmell in the Irish Peerage (becoming Earl Ligonier in 1776). On May 7, 1771 he fought a duel with swords in Green Park with the Italian poet Vittorio Amadeo, Count Alfieri (1749-1803), whom he suspected of adultery with his wife. He sued for divorce and the marriage was legally dissolved in 1772. Gazetted colonel of the 9th Regiment of Foot on August 8, 1771, he eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant general on August 29, 1777. On December 14, 1773 he married Mary Henley (d. 1814), third daughter of Jane (Huband) and Robert, 1st Earl of Northington. This marriage, like his first, was without issue, and when Lord Ligonier died at the age of forty-two on June 14, 1782 his title became extinct. He had devoted the last years of his life to lobbying for the "red ribbon" of Knight of the Bath, an honor that he finally gained on December 17, 1781, but he died before installation.

#portrait#full length#standing#landscape#horse#saddle#hat#sword#uniform#soldier#edward ligonier#viscount ligonier#boots#coat#biography#english#thomas gainsborough#british painter#british culture#18th century painting#oil on canvas#fine art#oil painting#european art#artwork#equestrian

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is #FlagDay! On this day in 1777, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Stars and Stripes as the flag of the United States. In 1949, President Truman signed an Act of Congress designating June 14 as Flag Day.

139 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flag Day commemorates the adoption of the flag of the United States on June 14, 1777 by resolution of the Second Continental Congress. The Flag Resolution stated "That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation."

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

EIGHT SURVIVING CHILDREN OF CARLO AND LETIZIA BONAPARTE, SIBLINGS OF NAPOLEON I 🥺🌟♥️

254 years ago on this day, Napoleon Bonaparte, the first French emperor was born

On the occasion of his birthday, meet the Eight surviving children of Carlo and Letizia Bonaparte, who lived to adulthood

Letizia Bonaparte gave birth to 13 children between 1768 and 1784; five of them died, two at birth and three in their infancy...😥🥀

Among the 13 children, the first child who died was Napoleone Buonaparte, who was born on August 17, 1765 and died on the same day... The last child to die was Jérôme Bonaparte, who died 95 years after his eldest brother...

The registered names of all the children of Carlo and Letizia Bonaparte:

• Napoleone Buonaparte (born and died 17 August 1765)

• Maria Anna Buonaparte (3 January 1767 – 1 January 1768)

• Joseph Bonaparte (7 January 1768 – 28 July 1844)

• Napoleon Bonaparte (Later French emperor) (15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821)

• Maria Anna Buonaparte (14 July 1771 – 23 November 1771)

• A stillborn child (1773)

• Lucien Bonaparte (21 March 1775 – 29 June 1840)

• Maria Anna (Elisa) Bonaparte (3 January 1777 – 7 August 1820)

• Louis Bonaparte (2 September 1778 – 25 July 1846)

• Pauline Bonaparte (20 October 1780 – 9 June 1825)

• Caroline Bonaparte (25 March 1782 – 18 May 1839)

• Jérôme Bonaparte (15 November 1784 – 24 June 1860)

#Carlo Buonaparte#Letizia Bonaparte#Joseph Bonaparte#Napoleon Bonaparte#Lucien Bonaparte#Elisa Bonaparte#Louis Bonaparte#Pauline Bonaparte#Caroline Bonaparte#Jérôme Bonaparte

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Shot Heard Around the World Chapter 27

Stars and Stripes (Wattpad | Ao3)

Table of Contents | Prev | Next

June 2, 1777

New Connecticut had his official name now.

State of Vermont. The name filled him with a giddy excitement, even if he was still having trouble remembering to respond to it. However, considering some people called him Green Mountains, Vermont wasn’t too hard to remember.

“How does it feel to officially be the State of Vermont?” Liam asked. Vermont laughed.

“Strange. I’m sure I’ll get used to it in time, just right now…I’m more used to New Connecticut than Vermont,” he answered.

“I like Vermont better. Easier to say, and it won’t get you confused with the American state,” Liam pointed out. Vermont shrugged, nodding in agreement before frowning.

“Vermont? Mont? Are you okay?” Liam asked, immediately picking up on Vermont’s expression. Vermont nodded.

“Oui, I am. Just…thinking. About my Papa,” he said.

“Have you still not heard back from him?” Liam asked. Vermont winced.

“I…didn’t send the letter,” he said.

“What? Why not?” Liam asked, looking shocked, “He’s your father. Don’t you want to know him?”

“Of course I do! But I’m nervous he won’t like me…and I want our first communication to be in person. And I want…I want to prove that I am committed to the idea of my independence—and his independence—just as much as he is. I don’t want to come off as some little nation that broke away from him and decided I was too good to actually help fight,” Vermont explained, nervous.

He had heard many stories about the one parent whose identity he knew for sure. Until he figured out who his other father was—Britain or Quebec, United States was all he had.

He wanted—needed to make a good first impression. He wanted his Papa to want him, to hold him and be his father.

Vermont was very lonely. He didn’t want to drive anyone further away.

“What do you mean fight? Are you thinking of joining in America’s war on Britain?” Liam exclaimed, looking shocked and maybe just the slightest bit scared, too. Vermont nodded.

“I have a better chance of keeping my independence if Papa has his. This will allow me to meet him and form a good relationship with him. It’s a good plan, I know it. I don’t think the British will keep me alive if Papa loses,” Vermont explained. Liam let out a low breath.

“Has the government allowed this?” he asked. Not wanting to answer, Vermont looked away. “They haven’t, have they?”

“No. But I am going to do it anyway. This…I want to meet my papa. And I want to be a country. This is the best way to make this happen,” Vermont said, voice more confident than he felt.

“Alright then. But be safe.” Liam said. Vermont smiled.

“Don’t worry. I promise I will be.”

• ───────────────── •

June 14, 1777

United States was a mix of exhilarated and terrified. He was getting a new flag, a proper new flag this time, one to mark that he was a real country, no longer a colony that needed to cling to the Union Jack. No longer a nation that needed his father.

He was excited. It would hold the same stripes of his last flag, but this time, the canton in the corner of his face would not hold his father’s flag but a blue field with thirteen stars.

“It’s going to be amazing!” Delaware said, the excitement in his voice bringing a smile to United States’ face.

“And you won’t have the Union Jack anymore, meaning no one can ever call you a British colony ever again!” James said. United States had never heard the man this excited before.

“Only if we win,” United States murmured.

“We will. Have some faith, would you?” James asked, a joking tone in his voice. United States’ mouth quirked into a small smile before fading back to the worried expression that seemed stuck on his face.

United States was staring at his hands, the delicate lines of his Father’s flag creating the pattern of the Union Jack on his palms. They had looked this way for what must be seventy-odd years now. United States never expected them to change.

They used to make him proud, back before everything fell apart. He could look at them and smile, knowing that his father would be there to protect him, that he could be proud to be a part of his father’s empire.

“I am worried, James. I want to be independent…but I still love my Father. How can…I have never been without his flag before. I don’t…” United States trailed off, unsure of how to turn the storm of emotions raging within him into proper words.

“If you are destined to still be family, then he will love you without your flag on him. You don’t have to wear his mark to be his family. You’re still related. But you’re your own country now. You can’t have his flag if you really want him to take you seriously,” James said.

United States nodded, hands still held half curled in front of him.

Then, the colors seemed to twist. United States’ hands began trembling slightly as the red was consumed by the blue, leaving his hands primarily blue with white lines on them, so similar to his Uncle Scotland’s flag.

The white and blue seemed to dance as the white retreated to the center of his palms. On his left hand, out of that circle of white, five points erupted, forming a giant star. On his right hand, the circle of white broken apart into smaller circles—thirteen if United States had to take a guess—which repeated the process of having five points erupt from each circle.

The thirteen stars on his right hand danced around, going back and forth from the palm of his hand to the back of it—revealing that thirteen more stars rested on the back of his hand before all of them settled down, creating a circle of thirteen stars on the front and back of his hand.

United States smiled.

“Wow…I don’t remember it doing that the last time it changed,” James commented, sounding awed.

“I’ve never seen it do that,” United States said before turning his hands over, laughing slightly.

“Hey, Da, since I was the first state to declare independence, and I helped make sure our vote for independence was unanimous, can I be the big star?” Delaware asked, excitement and mischief in his voice. United States laughed.

“Now Delaware, that’s not fair,” he said, “Besides, the big star already represents someone.”

“It does? Who? The Vermont kid that is almost definitely your kid?” James asked.

“No. It’s you, James,” United States said.

“ME? But I’m just a human. I have no reason to be on your…I…” James trailed off, seemingly at a loss for words.

“I want it to be you. Because you’re here with us, and countryhuman or not, you’re a part of this family. You deserve a spot on the flag. And here it has gone and presented us with a perfect opportunity to have you represented with part of it,” United States said, finding himself meaning every word.

“Thank you,” James said, sounding touched. “Thank you so much.”

“I’m going to go tell everyone else that Uncle James is on our flag!” Delaware said, and United States chuckled.

He was still anxious but happier.

“You’re going to keep that flag. Just like you’ll keep your independence,” James said reassuringly.

“I hope you’re right,” United States said before curling his hands into fists. “I really hope you are.”

• ───────────────── •

July 6, 1777

Nova Scotia was sitting in Fort Ticonderoga, the fort recently captured by the rebels. While some of General Burgonye’s troops were chasing down the fleeing rebels, Nova Scotia had been ordered to stay behind in the fort, as they thought those activities were not fit for a woman. Nova Scotia had scoffed but done what she was told.

Nova Scotia was glad that the rebels had abandoned the fort. She knew why her cousin’s rebellion had to be put down, but she loved Thirteen Colonies dearly and did not want to risk ruining their relationship.

But she didn’t get a choice not to go to war. Her king had ordered all British colonies in America to do their best to recapture their wayward family member, so off to war she went.

At the very least, her son got to be with her. He was only eight years old, even if he was physically fourteen, and Nova Scotia didn’t want to be parted from him.

“Màthair?” Saint John’s Island called.

“Yes, Eòin? What is it?” Nova Scotia asked.

“Do you think that we’ll have to fight Uncle Thirteen? I mean, I knew we were going to war with him, but it didn’t seem real until we took his fort, I know…I know what he’s doing is wrong, but I don’t want to hurt him,” her son said, looking scared, as if his fears were teason.

“I don’t want to hurt him either. I hope…I hope that we can take care of the rebels here without running into Edward, but I am…cautious to think that,” Nova Scotia said, sticking her hand onto her pocket where Thirteen Colonies’ letter sat. Nova Scotia had done as he asked, in case he really managed to do the impossible and win.

She didn’t think he would, but Britain was petty and vindictive and had already taken away Thirteen Colonies’ things for his earlier actions before her cousin had decided on full-blown treason. Nova Scotia just took them away before he destroyed them.

“Do you think that Britain will…will kill him?” Saint John’s Island asked, voice dropping to a whisper as he sat down beside Nova Scotia. Nova Scotia sighed, running her hand through her son’s hair.

“I hope not. He is a man full of anger, but…he still loves Edward in his own strange way,” Nova Scotia said, wondering if she was saying that just to convince herself. A part of her wondered if Thirteen Colonies only went along with this independence plan because he was afraid he would be killed if he came back.

While it was a forbidden topic in their household and a story that Saint John’s Island had certainly never heard before, Nova Scotia was reminded of New England Confederation and her bloody fate.

Thirteen Colonies had never been the same after she died. Jersey and Nova Scotis had comforted him through that time, and he always seemed empty, horrified, or furious.

Nova Scotia wondered if part of this was anger that had been building since New England Confederation’s death. It would make sense if it were.

But she couldn’t begin to understand what was going through Thirteen Colonies' mind right now.

“So Uncle Thirteen will live?” Saint John’s Island asked. Nova Scotia pulled him into a gentle hug and kissed his forehead.

“Yes, he will, Eòin. Don’t worry about that. This is to reunite our family, not destroy it,” Nova Scotia said.

She hoped Thirteen Colonies would be okay when everything settled.

#countryhumans#statehumans#countryhumans america#historical countryhumans#the shot heard around the world by weird#statehumans nova scotia#statehumans vermont

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy President’s Day! Fun facts that weren’t taught in US history classes, in the US public school education. There were 14 presidents before George Washington. They were apart of what was then known as the Continental congress and the Confederation Congress and they were elected by the delegates.

Peyton Randolph: Sep. 5 – Oct. 22, 1774

Henry Middleton: Oct. 22 – Oct. 26, 1774

Peyton Randolph: May 10 – May 24, 1775

John Hancock: May 24, 1775 – Oct. 31, 1777

Henry Laurens: Nov. 1, 1777 – Dec. 9, 1778

John Jay: Dec. 10, 1778 – Sep. 27, 1779

Samuel Huntington: Sep. 28, 1779 – Mar. 1, 1781

Samuel Huntington: Mar. 2 – July 6, 1781

Thomas McKean: July 10 – Oct. 23, 1781

John Hanson: Nov. 5, 1781 – Nov. 3, 1782

Elias Boudinot: Nov. 4, 1782–Nov. 3, 1783

Thomas Mifflin: Nov. 3, 1783 – Nov. 30, 1784

Richard Henry Lee: Nov. 30, 1784 – Nov. 4, 1785

John Hancock: Nov. 23, 1785 – June 5, 1786

Nathaniel Gorham: June 6, 1786 – Feb. 2, 1787

Arthur St. Clair: Feb. 2 – Oct. 5, 1787

Cyrus Griffin: Jan. 22, 1788 – Mar. 2, 1789

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

This Day in History: Stars & Stripes Saluted for First Time

On this day in 1778, the Continental Navy sloop Ranger sails into a French bay, proudly flying the American flag. It fires 13 guns, saluting the French fleet anchored there. The French flagship returns the salute, firing 9 guns of its own.

It was the first time a foreign nation ever saluted the Stars and Stripes.

Our flag was then still relatively new, having been adopted by the Continental Congress mere months earlier. “[T]he flag of the thirteen United States,” Congress resolved on June 14, 1777, “be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white” and “the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.”

Congressional delegates appointed John Paul Jones to command Ranger the very same day.

The story continues here: https://www.taraross.com/post/tdih-stars-stripes-saluted

#tdih#otd#this day in history#history#history blog#America#USA#American Revolution#stars and stripes#American flag#sharethehistory

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

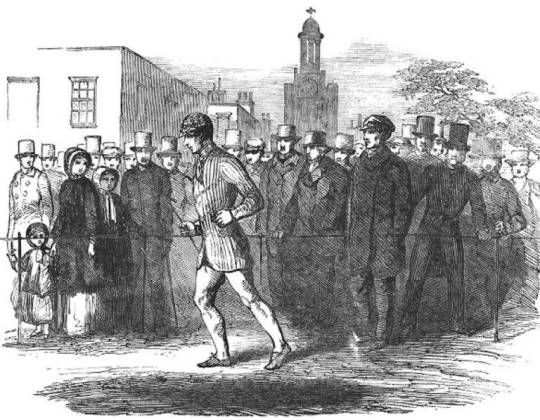

On May 8th 1854 Captain Robert Barclay Allardice died.

This is a great wee story about a very remarkable man, Robert Barclay Allardice has been called The Father of Pedestrianisma strange title, but when you learn his story you will maybe understand it better.

He was born in August 1777 at Ury House just outside Stonehaven Aberdeenshire to a family of athletes that in the past were practicing bull wrestling, carried flour sacks in their teeth, and uprooted trees with their bare hands. Robert Barclay Allardice was schooled in England and attended Cambridge University where he often gambled on the performances of other men, but also would often back himself to perform incredibly demanding physical challenges.

He took part in a number of bizarre pedestrian contests. In 1800 he backed himself to accomplish 90 miles within 21 hours, but he failed due to heavy rain and mostly because he caught a cold. He lost a thousand guineas, but didn’t give up and increased the stake to 2,000 guineas, and lost again. He backed himself again to the tune of 5000 guineas to perform the same feat and finally won with an hour to spare.

He won his first competition when he walked for 110 miles in 19 hours and 27 minutes. He also walked 90 miles in 20 hours and 22 minutes, the same year. In 1802 he walked 64 miles in 10 hours and in 1805, between breakfast and dinner, he walked 72 miles.

Among his many bizarre pedestrian contests, there was one when he walked 110 miles over bad roads in 19 hours and another in 1808 when he walked 130 miles without any sleep for two nights.

However, he made his epic walk at Newmarket in 1809 when he walked a mile in each of the 1000 consecutive hours. This meant that he was supposed to walk a mile per hour, every hour, for 42 days and nights. It all started on June 1st, 1809, and was completed on July 12th.

He walked his first mile in 14 minutes and 54 seconds and his time averaged 21 minutes and 4 seconds by the last week. During this period of 42 days and nights over 10,000 people watched the event. He completed the feat on 12th July in front of an enormous crowd that gathered to cheer him.

It is said that during this period he lost around 15kg, but didn’t regret since he won a large purse for his efforts.

During the Napoleonic War, he was commissioned in the army where he adopted the name, Captain Barclay. In 1809 he served as aide-de-camp to the Marquess of Huntly on the ill-fated Walcheren campaign, starting out just 5 days after the completion of the 1000-mile feat.

He was also interested in boxing and became trainer and sponsor of Tom Cribb, the bare knuckles Champion of the World in 1807 and 1809.

Im May 1854 Captain Barclay, the father of pedestrianism, a precursor to racewalking, was kicked by a horse in and died several days later from paralysis..

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stars and Stripes

Country: The United States of America

Contains: 13 stripes of alternating red and white. 50 white stars on a blue background in the top left corner.

The 13 white and red stripes signifies the original thirteen British colonies on the side of the Atlantic, and the 50 white stars represents the 50 new states that exist in the present USA. Each time a new state is officially created, a new star is added to the blue field in the flag.

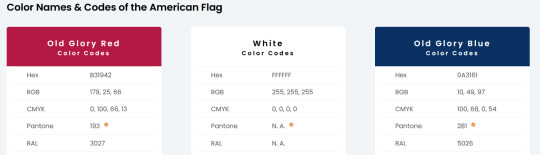

Colour code:

Origin: debatable Creator: under argument Adopted in: June 14, 1777

The coinage of the term 'Stars and Stripes' is credited to Marquis de Lafayette.

Flag History:

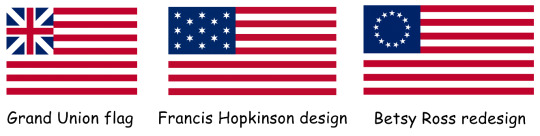

(Left) The grand union flag, when America was a colony under British rule. (Middle) The Francis Hopkinson design for 13 stars and 13 stripes (Right) Betsy Ross design featuring 13 stars arranged in a circular pattern

Evolution of the American flag over the time, and through the addition of new states.

References:

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who is the worst founding father? Round 4: Benedict Arnold vs Henry Clay?

Benedict Arnold (14 January 1741 [O.S. 3 January 1740] – June 14, 1801) was an American-born military officer who served during the Revolutionary War. He fought with distinction for the American Continental Army and rose to the rank of major general before defecting to the British side of the conflict in 1780. General George Washington had given him his fullest trust and had placed him in command of West Point in New York. Arnold was planning to surrender the fort there to British forces, but the plot was discovered in September 1780, whereupon he fled to the British lines. In the later part of the conflict, Arnold was commissioned as a brigadier general in the British Army, and placed in command of the American Legion. He led the British army in battle against the soldiers whom he had once commanded, after which his name became, and has remained, synonymous with treason and betrayal in the United States.

Historians have identified many possible factors contributing to Arnold’s treason, while some debate their relative importance. According to W. D. Wetherell, he was:

[A]mong the hardest human beings to understand in American history. Did he become a traitor because of all the injustice he suffered, real and imagined, at the hands of the Continental Congress and his jealous fellow generals? Because of the constant agony of two battlefield wounds in an already gout-ridden leg? From psychological wounds received in his Connecticut childhood when his alcoholic father squandered the family’s fortunes? Or was it a kind of extreme midlife crisis, swerving from radical political beliefs to reactionary ones, a change accelerated by his marriage to the very young, very pretty, very Tory Peggy Shippen?

---

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777 – June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state. He unsuccessfully ran for president in the 1824, 1832, and 1844 elections. He helped found both the National Republican Party and the Whig Party. For his role in defusing sectional crises, he earned the appellation of the “Great Compromiser” and was part of the “Great Triumvirate” of Congressmen, alongside fellow Whig Daniel Webster and John C. Calhoun.

[Clay and his family] initially lived in Lexington, but in 1804 they began building a plantation outside of Lexington known as Ashland. The Ashland estate eventually encompassed over 500 acres (200 ha), with numerous outbuildings such as a smokehouse, a greenhouse, and several barns. Enslaved there were 122 during Clay’s lifetime with about 50 needed for farming and the household.

In early 1819, a dispute erupted over the proposed statehood of Missouri after New York Congressman James Tallmadge introduced a legislative amendment that would provide for the gradual emancipation of Missouri’s slaves. Though Clay had previously called for gradual emancipation in Kentucky, he sided with the Southerners in voting down Tallmadge’s amendment. Clay instead supported Senator Jesse B. Thomas’s compromise proposal in which Missouri would be admitted as a slave state, Maine would be admitted as a free state, and slavery would be forbidden in the territories north of 36° 30’ parallel. Clay helped assemble a coalition that passed the Missouri Compromise, as Thomas’s proposal became known. Further controversy ensued when Missouri’s constitution banned free blacks from entering the state, but Clay was able to engineer another compromise that allowed Missouri to join as a state in August 1821.

#founding father bracket#worst founding father#founding fathers#amrev#brackets#polls#benedict arnold#henry clay

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Today is Flag Day. The annual commemoration is in honor of the adoption of the flag of the United States on June 14, 1777 by resolution of the Second Continental Congress.Here we see President Nixon and Special Assistant Robert J. Brown with an American flag from the Watts Manufacturing Company. (Image: WHPO-5234-07; 12/8/1970)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I visited family near Albany this weekend, and while exploring a historic cemetery I stumbled across a RevWar general, and one who features prominently in my future 5th Revolution book set during the Siege of Fort Schuyler (Stanwix). I only noticed it because I thought, "that stone looks old, oh it says 1777 and there's a flag, I should go look!"

The inscriptions read:

He served under Montgomery in Canada in 1775 In 1777 defended Fort Stanwix against St. Ledger thereby preventing his junction with Burgoyne and died in active command at the beginning of the war of 1812

To the memory of Peter Gansevoort Junior a Brigadier General in the army of the United States who died on the 2nd day of June 1812 aged 62 years 11 months and 16 days

Here Stanwix chief and brave defender sleeps

And the side for his wife:

Catherine van Schaick wife of Peter Gansevoort Jr. Died Dec. 30 1830 aged 78 years 4 months and 14 days [I think]

#albany rural cemetery#accidental research trip#my aunt got to hear a lot about history she probably didn't care about#peter gansevoort#revwar#american revolution#amwriting historical fiction#histfic#history is all around you

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Happy Flag Day

Flag Day is celebrated on June 14. It commemorates the adoption of the flag of the United States on June 14, 1777, by resolution of the Second Continental Congress.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Long May You Wave, Old Glory.

Long May You Wave, Patriots of America.

Country est. July 4, 1776

Flag est. June 14, 1777

2 notes

·

View notes